Ronald Lindsay retired from the British Ambassadorship in Washington and set sail for England on 30 August 1939, landing just after war was declared on Germany. Elizabeth Lindsay never saw her husband again. His work and failing health confined him to his country for the duration. He died in 1945 and was buried next to his first wife and her mother (Elizabeth Cameron had passed away in August 1944) in the small graveyard at Stepleton House in Dorset. The loyal and thoughtful Mildred Bliss had sent a friend to ensure that the monument was properly set.

Elizabeth Lindsay had gone to New York from Washington for family and business matters, intending to follow Sir Ronald and reunite with her aunt at Stepleton. But war-time travel restrictions and being (in her words) neither “fish nor flesh” (an American married to a British citizen), and her health kept her on the other side of the Atlantic, away from the beloved Dorset home and Paris.

The new ambassador, Philip Kerr, 11th Marquess of Lothian, arrived in August 1939, marking the beginning of a different period for the Embassy’s gardens. Lothian faced the delicate task of both maintaining and expanding American material aid despite the Neutrality Laws enacted by the United States Congress. Lothian sought a higher public profile (Lindsay never held a press conference until the impending Royal visit), and appealed directly to the whole populace to forge a closer understanding between the two countries. This intent is well illustrated by the unmarried Ambassador hosting on 10 June 1940 the first-ever garden party open to the public at the British Embassy. Unexpectedly for the planners, there was a huge turn-out: between 4,000 to 5,000 visitors attended, paying one dollar for admission, to raise funds for the “Bundles for Britain” organization, an American relief agency.

“British Ambassador dons full regalia for Diplomatic reception at White House”, 14 December 1939 (Harris & Ewing photograph, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

This public tea was also the first use of the additional land of the two lots bordering the garden on Massachusetts Avenue. The property had been quietly acquired in 1930 and incorporated into the grounds only in 1940, although Lady Lindsay had earlier planted the oak trees there and, as evidence from aerial photographs of the decade, the grounds were tended.

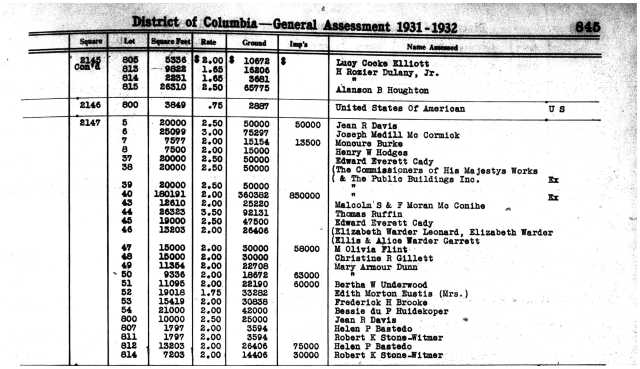

This important detail was first discovered by architect and diplomatic historian Mark Bertram, a fact buried in the Office of the Works correspondence files. Perhaps it was an effort avoid embarrassment for not acquiring the undeveloped land earlier, hence altering Lutyens’s design by the lack of a challenge of a 200-foot entrance. During this period, the Lindsays would have had to have covered some if not all of the costs of incorporating the land into the rest of the gardens. Misleadingly, a plaque in the wall near the greenhouses reads: “East of this Point 40000 Square Feet of British Government Property were added to the Embassy Garden in April 1940 by gift of Philip, 11th Marquess of Lothian His Majesty’s Ambassador to the United States 30th August 1939 – 12th December 1940”. Then again, those words could be interpreted as meaning the landscaping was done with funds by Lothian. But the deed and assessment records in the District of Columbia Office of the Surveyor confirm that the British Government actually purchased the land. The seller was the socialite and mystery writer, Mary Roberts Rinehart, who was frequently in need of funds.

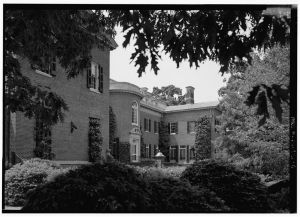

British Embassy, photo by Theodor Horydcazk, undated (Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

The multitudes for the “Bundles for Britain” event that were accommodated by the opening up of this area helped make the event a clear public relations success. The Washington Post (10 June 1940) noted whereas “officials of the British Embassy, which has had a reputation for snobbishness in the past,” were now at the fore front of putting embassies to charitable work, something that became a standard feature of the Washington diplomatic scene.

The Christian Science Monitor described the scene that June:

Guests wandered about the gardens, laid out by Lady Lindsay, wife of Lord Lothian’s predecessor. The roses, in which Lady Lindsay specialized, were at their height, and on the upper terrace the blue-line swimming pool furnished a cool spot for a brief pause. A large addition to the Embassy Garden, cleared and planted at the direction of Lord Lothian after the shortage of space at last year’s party for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, was used for the first time yesterday (10 June 1940).

Among the members of the sponsoring committee for the “Bundles for Britain” party were Robert and Mildred Bliss of Dumbarton Oaks and the wife of the American (“on-site”) architect of the Embassy, Frederick Brooke. Several other relief organizations and outside groups soon followed with similar events in the Embassy gardens during the war years.

Given the general economic uncertainty with the impending war, the Lindsays’s close friends and neighbors Robert Woods and Mildred Bliss deeded Dumbarton Oaks to Harvard University in 1940, earlier than they initially planned. Twenty-seven acres of the more informal, naturalistic landscape on the lower edge of the property (closest to the Embassy) were broken off from the estate and donated to the National Park Service, now Dumbarton Oaks Park. An elegant party marked the transfer, the Washington Post noting that “Scores of notables from out of town and a sizable section of social and official Washington were on hand to enjoy the event … Lady Lindsay came down from New York to attend the reception.” (2 November 1940).

Beatrix Farrand began in 1941 her Plant Book for the detailed, long-term maintenance of the Dumbarton Oaks landscape. To help continue the care of the Embassy gardens, in late 1938 or 1939, Lindsay hired a French gardener, Henri Blanleut, who had worked in the gardens of Versailles, and, after a stint in the French army, with the American Field service. After working on the estate of Col. Elisha F. Riggs, Blanleut was at the National Capital Parks when he met Lady Lindsay while tending roses. She probably recognized a talent to maintain the most demanding and time-consuming element of the gardens once her own tenure was over.

Notes & Bibliography

Dumbarton Oaks, view from the northeast (Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress)