After leaving Washington and diplomatic life, Elizabeth Lindsay was to finally have a home and garden entirely of her own making. She initially intended to stay in New York for only a while before following Sir Ronald to England. But with the outbreak of war, the condition of her own health and unspecified “family problems,” her State-side base, ‘Lime House,’ became her final place.

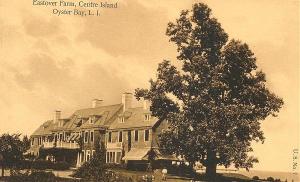

‘Lime House’ arose on forty-six acres on Centre Island, New York, carved out of the old family estate that took up a quarter of the island. The earlier mansion of ‘Eastover’ had been torn down in 1930—truly marking the end of the country place era in America—the year she had moved into the Lutyens Embassy in the nation’s capital. At that time, as vice president of the family owning corporation to develop ‘Eastover’, Lindsay had brought in the Olmsted Brothers of Brookline, Massachusetts to prepare the landscape for a scattering of small estates.

It was on the spot where the stables and her first landscape office had been located, with an allée of linden trees that she had planted years ago, where she constructed her “house-let”. Interesting plants that she had started from seed at the Arnold Arboretum thirty years earlier were moved from other parts of the property to her new garden.

There was a rose garden, of course, with brick walls she based on those of Middleton Place in South Carolina, considered to be the first landscaped garden in America. Perhaps the Lindsay rose as well as the lilac ‘Lady Lindsay,’ bred and introduced in 1943 by T. A. Havemeyer, an amateur horticulturist and garden writer, found a place there. As for herself, she wrote to Mildred Bliss: “I am pretty well settled in my house-let; & on the whole am content. Roots are strange things, and the sap flows more easily if the stem is with the roots. Whether it will bear leaves remains to be seen.” (3 August 1941).

Lilac ‘Lady Lindsay’ (Syringa vulgaris). Photo courtesy of the archives of the Lottah Nursery, Tasmania, Australia

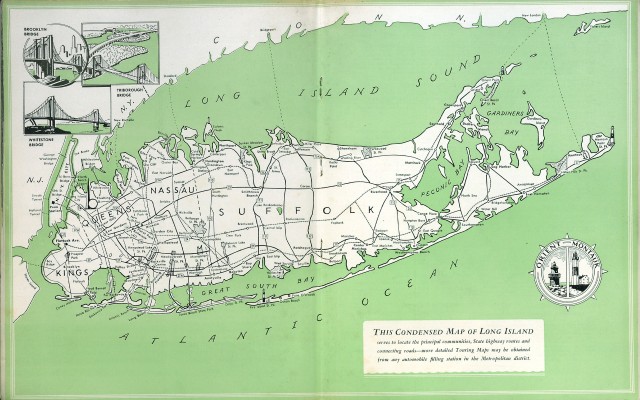

Even with her poor health (in addition to her long history of heart ailments, she was in a great deal of pain due to cancer), Lindsay managed a fair amount of work related to the war—for the British Library of Information, America Women’s Volunteer Services, Civilian Defense, and the Committee for the Care of European Children. Her old friend (remarried again) Isabella Greenway King wrote to a secretary on 27 January 1942: “If the occasion ever allows, will you tell Mrs. Roosevelt that her suggestion that we feed the Coast guard in our private homes when possible on their long watches is being put into practice. She would be interested to know that Lady Lindsay serves six meals in her house in Long Island during the twenty-four hours to these very men.”

Map from Long Island, the sunrise homeland. New York, 1940 (Dibner Library, Smithsonian Institution)

It was a sad end. On Long Island, Lindsay found, as have many before and since, that once out of power in Washington, one lost much of one’s standing in life. She wrote to Mildred Bliss: “And just now Beatrix [Farrand] has called me up, & roused a horrid feeling of envy. She is going to be near you, & I see green. Dear, dear Mildred; I wonder if you have any idea of how much I love you & admire you … Ronnie & Dilly [her aunt Cameron] write cheerfully, as do all my English friends & relatives” (20 November 1941).

Rather heart-breakingly, she continued: “I have no news … I also have no plans. I expect to stay here until January anyway. I may then be driven out by the over long evenings. In which case I might move into a hotel bed room in N.Y., or in Washington; == or I might wander. If I should (& could) take to wandering I might well head in your direction [Santa Barbara].” Lindsay had admitted earlier “I am homsek for Washington & ‘the swim’ beyond description. I ache for it, but I must not go.” (undated letter from Hayfields House, Oyster Bay, probably late 1939).

But Lindsay was soon in Washington staying with the Blisses in January 1940. She notified Bliss again that she was returning in May while admitting “I honestly dread seeing Washington in its spring garb. There is no sense in stirring up those feelings.” The Washington Times had once reported: “She arises at 6 o’clock in the morning and spends from four to six hours a day working on the flowers. According to the chatelaine of the embassy, there is no place on earth like Washington in the spring.” (23 April 1938).

Lindsay and Farrand, although both of self-deprecating character, had frustrating, lonely, last years, removed from Washington more and more as their previous formal roles there were over. Sir Ronald and Max Farrand both died in the same year (1945). Lindsay missed her active life and being surrounded by engaged, intelligent players. Farrand’s husband’s passing sent her into a very difficult time in her life, as their plans for the study center at Reef Point in Maine fell apart and she searched for a permanent home for her working papers. In their final years both women lived quiet lives, by the ocean and with their informal, personal gardens—their last creations.

Farrand died at her Garland Farm in Bar Harbor, Maine in 1959. After some trouble, her working and extant personal papers found a home in the Environmental Design Library at the University of California, Berkeley and at Dumbarton Oaks. Her legacy is well-documented in existing and maintained gardens, her own writings and the biographies and monographs of her life and professional work. And, of course, in the great American garden—Dumbarton Oaks.

Lindsay’s travels in her later years were confined to New York City and Washington. She passed away at ‘Lime House’ in 1954 at the age of sixty-eight. For a woman who had been so much in the news fifteen years earlier, and whose engagement announcement ran seven paragraphs in the New York Times (8 July 1924), the few obituaries were short—death notices really. The Times note gave her gardening equal measure to any other aspects of her life: “Lady Lindsay was a landscape gardener by profession.”

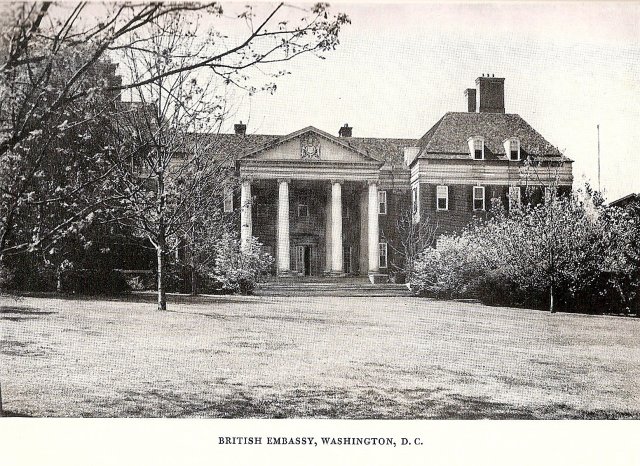

Lindsay faded from public life rather quickly and her achievements are now largely seen with secondary evidence at best. The editor of her letters, Olivia James, summarizing her early landscaping career, concluded: “On the whole, she was successful on a modest scale and could have gone far had not World War I called her to other activities.” Her most visible legacy can be seen today in traces of the British Embassy gardens. Among her work that remains are some of the yews that used to circle the large tennis court area; a tulip poplar, likely planted in 1931, stands near there. Of Lindsay’s beloved cherry trees, under which a red-coated, pith-helmeted Exeter band stood to play during the Royal visit, only six gnarled ones survive.

Lady Lindsay took thousands of photographs, at the Embassy and other places “in defense of beautiful memories of beautiful place” (Washington Post, 21 May 1939). In a Bliss letter, “I came to your garden today, sans a coloured film alas, but Alice Longworth & I (fresh from falling into the Canal) rejoiced in your Japanese maple, & in our mutual feeling for you.” The Washington Post wrote of her: “Amateur photography is another of her special interests … She has made camera studies of virtually every leafy nook, every flower-fringed corner of the garden that in a way is a monument to her love of the beautiful and her skill in achieving it” (21 May 1939).

Unfortunately, the location of her papers, photographs and other records is not currently known and they may have been destroyed after her death or the publication of James’s book. They would provide a visual plant book of the British Embassy gardens at their creation.

British Embassy from garden, photo by Theodor Horydczak (Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

Lindsay took care that her plantings at the Embassy would not require overwhelming maintenance and would guide her successors over the years. But perhaps no other existing garden in Washington, except at the White House, have had so many changes, with a constantly changing roster of participants, and different visions and demands—including, of course now, higher security.

Taking on a rather cold, forbidding place, Lindsay provided the necessary elements for softening Lutyens’s structure, finally finishing the design with a suitable English-inspired landscape, the plantings contributing a sense of balance and completeness to the complex. With both the house and gardens fitted into the contour of the site and the use of traditional, local materials, later softened by the plantings, there came to be a nostalgic, secluded feel to the landscape that is essential to the Lutyens-Jekyll aesthetic, creating more a world of its own. Burdened with inadequate resources, the joined buildings of the Residence and Chancery were barely completed by the time of their occupancy in 1930, which meant the landscape, crucial to the design as a whole was neglected. Only once the gardens were properly planted did Lutyens’ distinctive structure fully come into its own.

And more than anyone else, the person who made that happen was a product of the affluent period of American growth, confidence and ambition: Lady Lindsay created the working yet beautiful setting that came to be the practical, visible representation of Great Britain and a famous English garden in the United States. This was the golden era of the Ambassador’s Residence gardens.

Notes

Lindsay wrote to Mildred Bliss on 7 August 1939 from Woodbury, Long Island:

Dearest … We (Irene & I) are luxuriously parked here, & are beginning to catch our breath. Ronnie comes & goes; & hopes to sail the end of August. On the excuse of family business (true enough God knows) I am looking for a small house on Long Island to rent for the winter. During that time I shall try to find a permanent perch somewhere for “part of every year.” That is the only ammunition I can use or offer my loyal friends – a. Family business requires my presence in the immediate future. B. I purpose buying a country pied à terre in which I hope to spend part of every year in the future. No one should be startled if they hear of my having bought something therefore. (The Papers of Robert Woods Bliss and Mildred Barnes Bliss. Harvard University Archives HUGFP 76). A Washington Post article, entitled “News out of former capitalite”, began:”’Whatever has become of Lady Lindsay?’ is a question often heard over tea cups when reminiscences are in order. One of the most unpopular and at the same time most loved wife of the former British Ambassador, Sir Ronald Lindsay, seems to have completely dropped out of the Washington picture. Some say she’s living in Virginia …”. (Marie McNair, 29 October 1944).

Havemeyer had an outstanding collection of lilacs at his Cedar Hill Nursery Estate in nearby Brookville. The New York Botanical Garden maintains the T.A. Havemeyer Lilac Collection, with 90 different kinds. For more on him see Lilacs: a gardener’s encyclopedia, vol. 35, by John L. Fiala (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 2008).

This promotional video of Middleton Place Plantation shows the brick work: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=82-PhKin1B4

James, Olivia, edited by. The letters of Elizabeth Sherman Lindsay, 1911-1954. New York: Privately printed, 1960.

“Small estates planned on Center Island tract”, The New York Times (19 July 1940).