Colgate Hoyt and second wife (?), Katherine Sharp Perin, ca. 1915 (Bain News Service; Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

The first ambassador’s wife to live in and influence the new British Embassy in Washington, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, was the spirited Lady Lindsay. She has born Elizabeth Sherman Hoyt and grew up and died on Centre Island, New York. The place was formative to her character and early career, instilling a love of the outdoors while providing her an introductory education in gardening and architecture, not only at her family’s estate but also with the landscapes of the fabulous Gilded Age mansions, most often of English, French or Italian inspiration, that were created on Long Island during her formative years. With a home in nearby Manhattan, family in Cleveland and Washington, D.C., Hoyt moved in a sophisticated and cultivated, if relatively small, world. With her father’s support, both practical and emotional, to extend herself somewhat beyond traditional women’s roles of the period, she could drive at the age of eleven, build and sail her own boat as a child, manage the estate of ‘Eastover’ while still in her teens and, eventually, to professionally design gardens.

Decades later, these skills would be put to excellent use when she married a British diplomat, widower of her cousin, who rose to become ambassador to the United States in 1930, Sir Ronald Lindsay. As Lady Lindsay, Elizabeth Sherman Hoyt became the efficient manager of the just-built Embassy and a central player in creating the famous gardens of the Ambassador’s Residence in Washington, D.C.

The North Shore, or Gold Coast, of Long Island during the country place era, from about 1880 to 1940, was second only to Newport, Rhode Island in its extravagant mansions and gardens. Centre Island is a small but extremely moneyed peninsula tucked in there, surrounded by Cold Spring Harbor, Oyster Bay and Long Island Sound, resembling a curved miniature Italy to some extent. Just thirty-two miles from Manhattan, the area was not easily accessible until a spur of the Long Island Rail Road was laid down to Oyster Bay in 1889. The Island became a summer colony for the well-to-do not unlike Bar Harbor and Southampton when the storied Seawanhaka Corinthian Yacht Club, founded at Centre Island in 1871, returned there from New York Harbor in 1892. Wealthy members, including Elizabeth’s father, Colgate Hoyt, soon followed, building country homes.

Seawanhaka Corinthian Yacht Club, photo 1905, by Frances Benjamin Johnston (Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

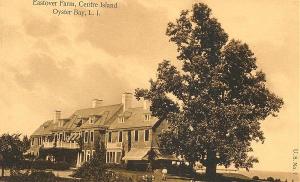

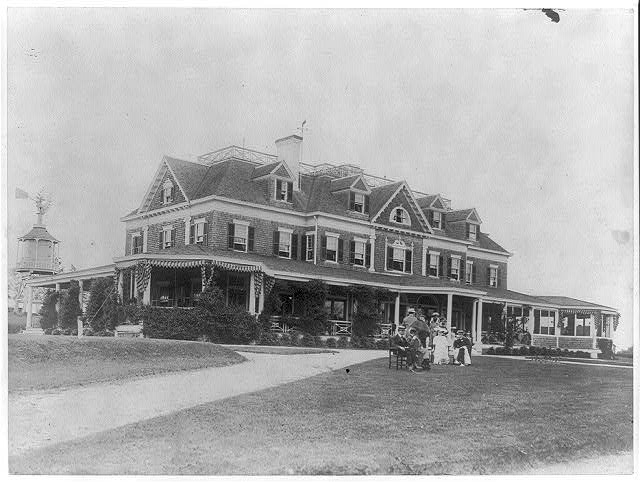

In Hoyt’s case, this meant buying up nearly a quarter of Centre Island for his estate, ‘Eastover’. The “farm” became the family’s principle residence while their Manhattan home was 121 Madison Avenue. As detailed in an earlier post, Elizabeth Hoyt initially set up her landscape business in a rented office at 171 Madison and at ‘Eastover’. Despite being near the Yacht Club, the Hoyt property had its own boathouse (torn down in 2008) and yacht landing and was, indeed, a self-sufficient enterprise. There was a modern dairy, stables, elaborate garage, working farm, orchard, vegetable and flower gardens, and an additional cottage of seven rooms. To ensure the privacy of its landowners and some control over property taxes, Centre Island was incorporated as a separate village with its own government within Nassau County in 1926 and parts were further designated as a bird sanctuary. It remains its own governmental entity today, with a private police force.

The first world-class competitive yachtsman in the United States, Charles Sherman Hoyt, learned to sail from Centre Island, as did his sister Elizabeth. Helming her boat Iris, she came in a close second in the annual (and only) race for women at the Seawanhaka Corinthian Yacht Club July 1914, a time when she was beginning her professional landscaping career. With Oyster Bay providing a sheltered harbor for all vessels, great sailing on the Sound out to the Atlantic, and with Block Island, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket all within easy reach, the area is a sailor’s— and an adventuresome child’s—paradise.

While the base of Centre Island launched her brother’s profession, Long Island was also an incredibly fertile place both for notable gardens and the start of Elizabeth Hoyt’s interest and first career, experience that helped prepare her for later planting the British Embassy gardens in Washington. As Griswold and Weller point out in their The golden age of American gardens:

A soft climate and hard cash made the gardens of Long Island opulent as well as beautiful … Ideally, a North Shore estate was situated on one of the little peninsulas in Oyster Bay or Cold Spring Harbor known as “necks.” Framed by the huge old trees that grew so abundantly in the region was a glimpse of the Sound on one side of the house and on the other a rolling country view carefully tailored from parcels of old farmland. Long Island has a fabulous garden climate and good soil because the entire island is one great long glacial dump … Long Island has the English equilibrium that lets perennials and tender shrubs thrive.” (p. 92)

The Shingle-style home of ‘Eastover,’ designed by the firm of Renwick, Aspinwall & Owen, and its surrounding land was Elizabeth Hoyt’s learning ground, but other estates on Long Island were there for her study and inspiration. Her close friends, the Bayard Cuttings, had ‘Westbrook’ (1887) on the South Shore, on the Connetquot River. Her mentor, Beatrix Jones (later Farrand) had a commission there for a flower garden in 1910 (but perhaps never planted). Elizabeth Hoyt, by then Lady Lindsay, was a trustee of the fund to establish the Bayard Cutting Arboretum in the 1930s (opened to the public in 1953). Her life-long friend and biographer, Olivia Bayard Cutting (1892-1963), had a short marriage to Henry James, the son of William James and nephew of author Henry James. Olivia’s father William was a financier but also a director of the New York Botanical Garden. His conifer collection was formed with the guidance of Charles Sprague Sargent of the Arnold Arboretum, where both Jones (Farrand) and Hoyt were tutored.

‘Planting Fields’, Oyster Bay, New York, Entrance gates to Blue Pool Garden and tea house. Photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1926 (Prints & Photographs Division, LC)

On the other side of Oyster Bay from ‘Eastover’ is the ‘Planting Fields’ (1913), the estate of Mai Rogers and William Robertson Coe, now, as is ‘Westbrook’, a public arboretum, the only two run by the state of New York. The Coes brought in the firm of the Olmsted Brothers of Brookline, Massachusetts for the landscaping, as did many other estates on Long Island (including ‘Westbrook’) and had a working relationship with the Arnold Arboretum.

‘Red Maples,’ Mrs. Rosina Sherman Hoyt House, Southampton, New York. Herbaceous garden and entrance to hedge garden. Photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1915 (Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

Elizabeth Hoyt’s relative, Alfred William Hoyt, hired the architectural firm Hiss & Weekes to build a home in Southampton around 1908. He died during construction but his wife and daughter, both named Rosina Hoyt, and—additionally confusing—the mother, Rosina Sherman Hoyt, was a cousin of Elizabeth Hoyt’s mother Lida Sherman. The two Rosinas finished ‘Red Maples’ and lived there until 1922. The landscaping was by Florence-born Ferruccio Vitale, whose career included the plantings for Meridian Hill Park in Washington, D.C. ‘Red Maples’ is no longer standing but is preserved, along with the gardens, in the photographs of Frances Benjamin Johnston. There are 1,130 hand-colored glass–lantern slides of her garden images, many of the Beaux-Arts period on Long Island as well as of less wealthy Americans homes, archived in the Library of Congress. Johnston, a celebrated photographer in her day, also captured life and society around Centre Island and the Yacht Club.

Yacht Club launch, Centre Island, 1905 photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

The estates of various European architectural styles on both the North and South Shores of Long Island required opulent gardens, which provided wonderful opportunities for the early professional women landscape gardeners, such as Elizabeth Hoyt. Some of her near contemporaries who worked in the area included the well-known and accomplished Ellen Biddle Shipman, Annette Hoyt Flanders, and Marian Cruger Coffin. From 1913, Farrand had several commissions on Long Island, including the Edward F. Whitney Residence in Oyster Bay. Still extant (unlike many of the properties of the period) is Farrand’s headstone for the grave of Theodore and Edith Roosevelt in the Youngs Memorial Cemetery, near Sagamore Hill, also in Oyster Bay. Before going to Washington and her work at the Red Cross during the Great War, Hoyt had some small commissions, no doubt from family and society connections, currently unknown in their locations.

By the time Sir Ronald Lindsay finally was allowed to retire from the British Ambassadorship in Washington (August 1939), Lady Lindsay sought an American base of her own on the land of her upbringing. Her father had died in 1922 and her three siblings lived in the general area. After attempts by the family to retain ownership and develop the property failed, a good portion of ‘Eastover’ was sold in 1929 to George N. Armbsy who had the main house torn down in 1930. However, in 1940 there was, oddly, a return to some type of family trusteeship of about 150 acres of the old ‘Eastover’. Lady Lindsay was vice-president of the corporation to develop the property and she brought in the Olmsted Firm to prepare the land. For herself, while staying at a couple of rental houses in other villages of Oyster Bay, in 1941 Lady Lindsay began to build her comfortable and wonderfully proportioned home on forty-six acres of the original ‘Eastover’. Lindsay named it ‘Lime House’ after the two rows of Tilia cordata (small-leaved lime or linden) that she had planted three decades earlier to form an avenue to what was then her landscape gardening office. At this time, she wrote to Mildred Bliss in Washington: “I am pretty well settled in my house-let; & on the whole am content. Roots are strange things, and the sap flows more easily if the stem is with the roots. Whether it will bear leaves remains to be seen.” (3 Aug 1941 Lime House, Centre Island, Oyster Bay, Long Island).

‘Lime House’ still stands, although the property currently consists of only nine acres; the other land—a large salt meadow and tidal creek where legend has it that Captain Kidd buried some treasure when moored nearby in 1699—was donated by Lindsay to the village for wetland preservation. The main part of the home is in brick, the remainder in wood, perhaps reflecting the scarcity of materials during the war. It was a decidedly different era than the Gilded Age of her youth. With few additions or changes, there are echoes of Lady Lindsay throughout the property: old trees and shrubbery including magnolia, dogwood and spectacular rows of linden trees leading from the road. Her rose garden remains but its brick work is mostly gone as is much of the patio that faced it. It was a far more casual garden than her plantings at the Washington Embassy, taking in the relatively “wild” surroundings and reflecting the time’s change in wealth and unavailability of labor, as well as her own relatively modest tastes.

Centre Island is an exceedingly private place, with new grand trophy homes—some approaching the Gold Coast extravagance of yore—dotting its four miles of coast line. Today, there are virtually no surviving traces of its fishing village and brick industry of years past. And reflecting its continued role as an extremely private and well-guarded retreat for the wealthy, there are no public buildings, parks or access.

Notes and Bibliography

Corresponded quoted form the Harvard University Archives, Papers of Robert Woods Bliss and Mildred Barnes Bliss, HUGFP 76.8, Box 28.

7 August 1939

Woodbury, Long Island

Dearest … We (Irene & I) are luxuriously parked here, & are beginning to catch our breath. Ronnie comes & goes; & hopes to sail the end of August. On the excuse of family business (true enough God knows) I am looking for a small house on Long Island to rent for the winter. During that time I shall try to find a permanent perch somewhere for “part of every year.” That is the only ammunition I can use or offer my loyal friends – a. Family business requires my presence in the immediate future. B. I purpose buying a country pied à terre in which I hope to spend part of every year in the future. No one should be startled if they hear of my having bought something therefore.

‘Planting Fields’ Oyster Bay. View from tea house to Blue Pool Garden. Photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston, Spring 1926 (Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

Griswold, Mac and Eleanor Weller. Golden age of American gardens: proud owners, private estates 1890-1940. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1991.

Hoyt, C. Sherman. Sherman Hoyt’s memoirs. New York: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc., 1950. Hoyt served in the Navy during both world wars; he studied naval architecture at Edinburgh University and helped design and test PT boats.

MacKay, Malcolm and Charles G. Meyer, Jr. A history of Centre Island. Privately published, 1976; second printing, 1980.

Roosevelt, Commodore J. James. A short history of the Seawanhaka Corinthian Yacht Club (1994).

S.C. Yacht Club Regatta, 20 June 1897, photo by John S. Johnston (Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress)